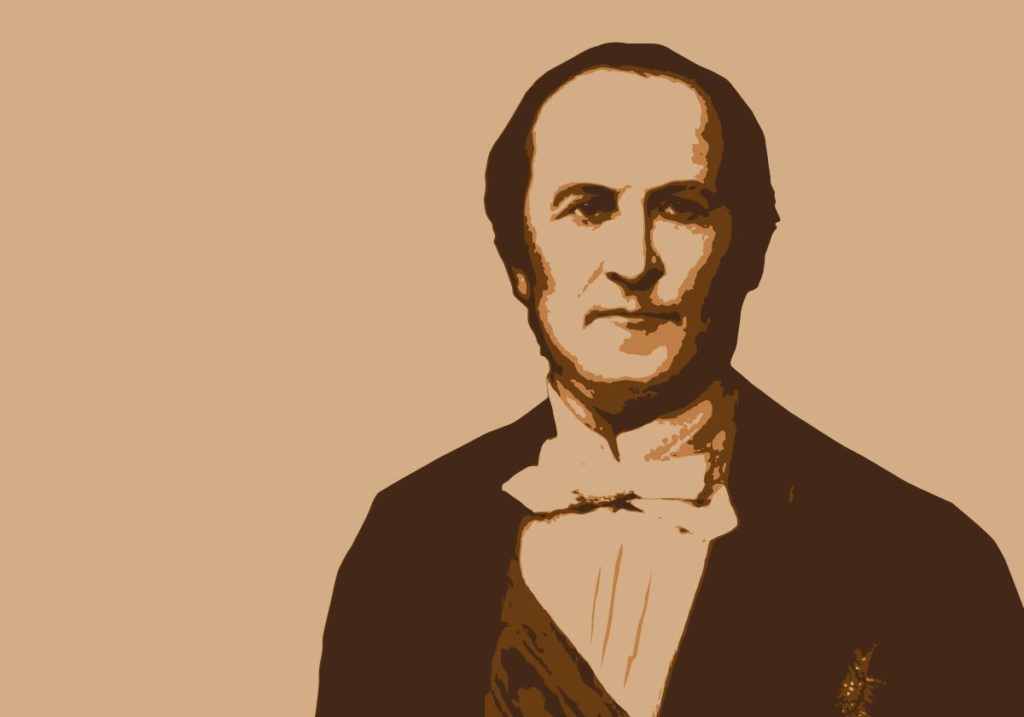

Haussmann the Architect, a visionary who changed Paris

Prince-President Louis-Napoleon Bonaparte tasked architect Georges Eugène Haussmann with constructing Paris the most beautiful city on the planet in 1853. The end effect is magnificent, with the French capital becoming cleaner, better supplied, and more ventilated. It also flourished tremendously, gaining structures of exceptional refinement that are still associated with status today. An examination of the history and many facets of these momentous shifts, whose traces continue to affect the history of Parisian real estate.

Baron Haussmann: a life in the service of France

If Haussmann’s enormous accomplishments were the result of indisputable and frequently shown personal brilliance, he profited from his birth, an environment, and favorable supports to chart a straight road to the top.

A childhood guided by a prestigious family

Georges Eugène Haussmann, who was born in Paris in 1809, comes from a Protestant-Lutheran family whose forefathers escaped persecution in Saxony and subsequently Alsace in the 16th century. His father was Napoleon I’s military intendant, and he was the son of Nicolas Haussmann, a member of the Legislative Assembly and the Convention, as well as the administrator of the Seine-et-Oise department. His mother was the daughter of Frédéric Dentzel, a commander and baron of the Empire.

Brilliant studies aided the start of his career, particularly as he had a strong acquaintance with the Duke of Orléans, Louis-oldest Philippe’s son, during these years, which would allow him to profit from his influence.

A rapid ascent to high state office

He served as sub-prefect of Nérac in Lot-et-Garonne from 1832, then of Saint-Girons in Ariège, and finally of Blaye in Gironde. He became prefect of the Var in 1849, then of the Yonne in 1950, and lastly of the Gironde in 1851. He oversaw key initiatives in Bordeaux, including the construction of railway lines, the founding of companies, the introduction of social support for single mothers, and the improvement of the lighting and water supplies.

After shining as a top official in numerous areas of France, it was in Paris that his talent was finally shown to its full degree. In 1853, he was named prefect of the Seine after being submitted to Napoleon III by Minister of the Interior Victor de Persigny.

A major renovation: how Haussmann changed Paris

Paris had not altered much since the Middle Ages in the mid-nineteenth century: most of its arteries were tiny, meandering alleyways, gloomy, and unclean. While wandering through the center of the city, you may easily come across several of these arteries that were not renovated during Haussmann’s time (but have, thankfully, gained in modernity!).

London, a role model

When the Emperor entrusted Haussmann with the repair of Paris, he was impressed by his visit to London, which had been rebuilt after the Great Fire of 1666 and had become a model of contemporary urban planning. From there, Haussmann began to define an ambitious project based on his observations of the English capital, aiming first and foremost to facilitate the flow of water and waste, as well as the population, through the city’s arteries – and, more subtly, to thwart a possible future revolt through an organization neighborhood.

Large (and long) boulevards, well organized

Haussmann planned to expand the network of key streets, such as rue Saint-Honoré, rue Saint-Martin, and rue des Italiens, and supply them with a true sanitation network in order to address the cleanliness and traffic issues. He also intended the streets to be broad enough for a taxi or an omnibus to pass through, with a walkway on either side to clear the center of the road of people.

The architect Haussmann, a follower of the straight line, or “cult of the axis,” planned a capital centered on vast avenues that ran from one end of the city to the other. As a result, they stimulate not only circulation and commerce, but also trash and waste water evacuation, which will profit from the modern sewage system that still exists today.

Many boulevards and avenues have been built in less than 20 years, from Place de la Nation to Place de l’Étoile, from Gare de l’Est to Observatoire, and so on. The Champs-Élysées were built at the same period, and Paris underwent a dramatic transformation.

An enlarged and modernized city

The first goal of making Paris prettier and more spectacular is met: the great historical sites are emphasized since they are in the axis of the new avenues, and the new structures conform with stringent rules, which we shall return to. On the Seine, bridges are also being erected to provide for a continuous passage.

Eleven bordering municipalities vanished and were absorbed by Paris in order to gain additional territory (La Villette, Belleville, Montmartre, etc.). Others were partially annexed: the city expanded to the Thiers Enclosure, a fortress erected during Louis-Philippe to prevent a foreign force from capturing the city.

The City and Chatelet theatres, as well as the Gare de Lyon and the Gare de l’Est, were built according to Haussmann’s concept. The religious legacy of Paris is further enriched by new churches.

Parks, so that Paris can breathe

While some existing green spaces have been harmed by the Haussmannian restoration since they are located along the straight lines of the avenues, parks and gardens are not ignored and are an important component of the urban architect’s approach.

In order to enhance the quality of life for Parisians, a park has been established in each of the city’s 80 districts. The Buttes-Chaumont and Montsouris parks open to the public, and the Boulogne and Vincennes forests become popular walking destinations.

Haussmannian elegance is inscribed on the buildings

Numerous demolitions and the erection of new, fully remodeled structures, the majority of which were apartment buildings or mansions, followed the Haussmannian alterations. Many property buyers in Paris still like to look for homes that have the qualities of this kind of building. Let’s take a closer look at what makes it unique.

A particularly elaborate exterior visual

Unlike other architectural forms, the Haussmann facade style is immediately identifiable. The foundation is made up of majestic ashlar facades that have been meticulously hewn in a linear pattern. The buildings’ height is determined by a computation based on the width of the street they overlook, and they must never exceed six stories.

The emergence of these floors isn’t random: each has a design that corresponds to their anticipated use. As a result, the bottom level, which is designed for stores, will have the maximum ceiling height. The first level, or “mezzanine,” was often utilized as a storage area for commodities during the period.

The second level was designed to house the building’s richest residents, with balconies, intricate moldings, and fine window frames. The architectural richness of the third and fourth levels is lost, but the general style is maintained. In certain circumstances, joinery may open into balconies.

The fifth level usually included a large balcony, although it was geared towards lower-income households. The sixth story was solely intended to house the servants.

Interior decorations aimed at elegance

Anyone entering a Haussmann-style flat will immediately recognize it as such, just as the outer façade does. Marble fireplaces, which are sometimes carved and have a modest footprint in the space, are a powerful aesthetic feature that stay in situ even after they are no longer used for heating.

Moldings that run the length of the walls or the base of the walls, the ceiling, and even the fireplaces give the different rooms a decorative elegance that is still popular today. These components may be found in a variety of spaces, not only the living room. The bedrooms, in particular, were as ornately sculpted as the rest of the house.

Finally, solid parquet in a herringbone or herringbone pattern warms the environment and is associated with quality: it can be sanded and has an almost infinite lifetime if properly maintained. It should be noted that decorative features characteristic of Haussmann architecture, such as the big carved mirror on the mantelpiece and other distinctive ornamental components, were added to these basic elements.

Between 1853 and 1870, Baron Haussmann oversaw a massive reconstruction of Paris that completely transformed the city. In less than 20 years, 20,000 unclean structures were demolished and 30,000 reconstructed, while 300 kilometers of roads and 600 kilometers of sewers were constructed. 60 percent of the city has been altered, according to estimates. Keep in mind that there were no bulldozers back then, thus everything was done with shovels, pickaxes, and the sweat of the laborers!